A recent

story about the holes in

Google's SLA got me wondering about the state of

service level agreements in the

SaaS space.

The importance of SLA's in the enterprise online world are obvious. I'm sad to report that of the state of the union is not good. Of the handful of major

SaaS players, most have no

SLAs at all. Of those that do, the coverage is extremely loose, and the penalty for missing the

SLAs is weak. To make my point, I've put together an exhaustive (yet pointedly short) list of the

SLAs that do exist. I've extracted the key elements and removed the legal

mumbo-jumbo (for easy consumption). Enjoy!

Comparing the SLAs of the major SaaS playersGoogle Apps:- What: "web interface will be operational and available for GMail, Google Calendar, Google Talk, Google Docs, and Google Sites"

- Uptime guarantee: 99.9%

- Time period: any calendar month

- Penalty: 3, 7, or 15 days of service at no charge, depending on the monthly uptime percentage

- Important caveats:

- "Downtime" means, for a domain, if there is more than a five percent user error rate. Downtime is measured based on server side error rate.

- "Downtime Period" means, for a domain, a period of ten consecutive minutes of Downtime. Intermittent Downtime for a period of less than ten minutes will not be counted towards any Downtime Periods.

Amazon S3:

- What: Amazon Simple Storage Service

- Uptime guarantee: 99.9%

- Time period: "any monthly billing cycle"

- Penalty: 10-25% of total charges paid by customer for a billing cycle, based on the monthly uptime percentage

- Important caveats:

- “Error Rate” means: (i) the total number of internal server errors returned by Amazon S3 as error status “InternalError” or “ServiceUnavailable” divided by (ii) the total number of requests during that five minute period. We will calculate the Error Rate for each Amazon S3 account as a percentage for each five minute period in the monthly billing cycle. The calculation of the number of internal server errors will not include errors that arise directly or indirectly as a result of any of the Amazon S3 SLA Exclusions (as defined below).

- “Monthly Uptime Percentage” is calculated by subtracting from 100% the average of the Error Rates from each five minute period in the monthly billing cycle.

- "We will apply any Service Credits only against future Amazon S3 payments otherwise due from you""

Amazon EC2:- What: Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud service

- Uptime guarantee: 99.95%

- Time period: "the preceding 365 days from the date of an SLA claim"

- Penalty: "a Service Credit equal to 10% of their bill for the Eligible Credit Period"

- Important caveats:

- “Annual Uptime Percentage” is calculated by subtracting from 100% the percentage of 5 minute periods during the Service Year in which Amazon EC2 was in the state of “Region Unavailable.” If you have been using Amazon EC2 for less than 365 days, your Service Year is still the preceding 365 days but any days prior to your use of the service will be deemed to have had 100% Region Availability. Any downtime occurring prior to a successful Service Credit claim cannot be used for future claims. Annual Uptime Percentage measurements exclude downtime resulting directly or indirectly from any Amazon EC2 SLA Exclusion (defined below).

- “Unavailable” means that all of your running instances have no external connectivity during a five minute period and you are unable to launch replacement instances.

...that's it!

Notable Exceptions (a.k.a. lack of an SLA)

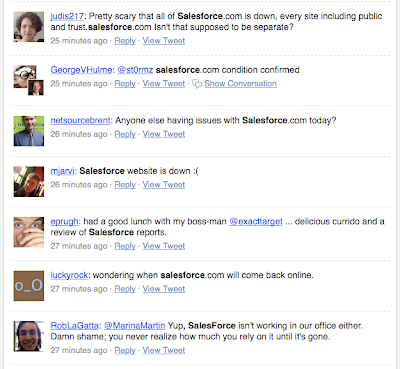

- Salesforce.com (are you serious??)

- Google App Engine (youth will only be an excuse for so long)

- Zoho

- Quickbase

- OpenDNS

- OpenSRS

ConclusionsThere's no question that for the enterprise market to get on board with

SaaS in any meaningful way accountability is key.

Public health dashboards are one piece of the puzzle.

SLAs are the other. The longer we delay in demanding these from our key service providers (I'm looking at you

Salesforce), the longer and more difficult the move into the cloud will end up being. The incentive in the short term for a not-so-major

SaaS player should be to take the

initiave and focus on building a strong sense of accountability and trust. As it begins to take business away from the more established (and less trustworthy) services, the bar will rise and customers will begin to demand these vital services from all of their providers. The day's of weak or non-existant SLAs for SaaS providers are numbered.

Disclaimer: If I've misrepresented anything above, or if your

SaaS service has a strong

SLA, please let us know in the comments. I really hope someone out there is working to raise the bar on this sad state.

+on+Twitter-1.png)